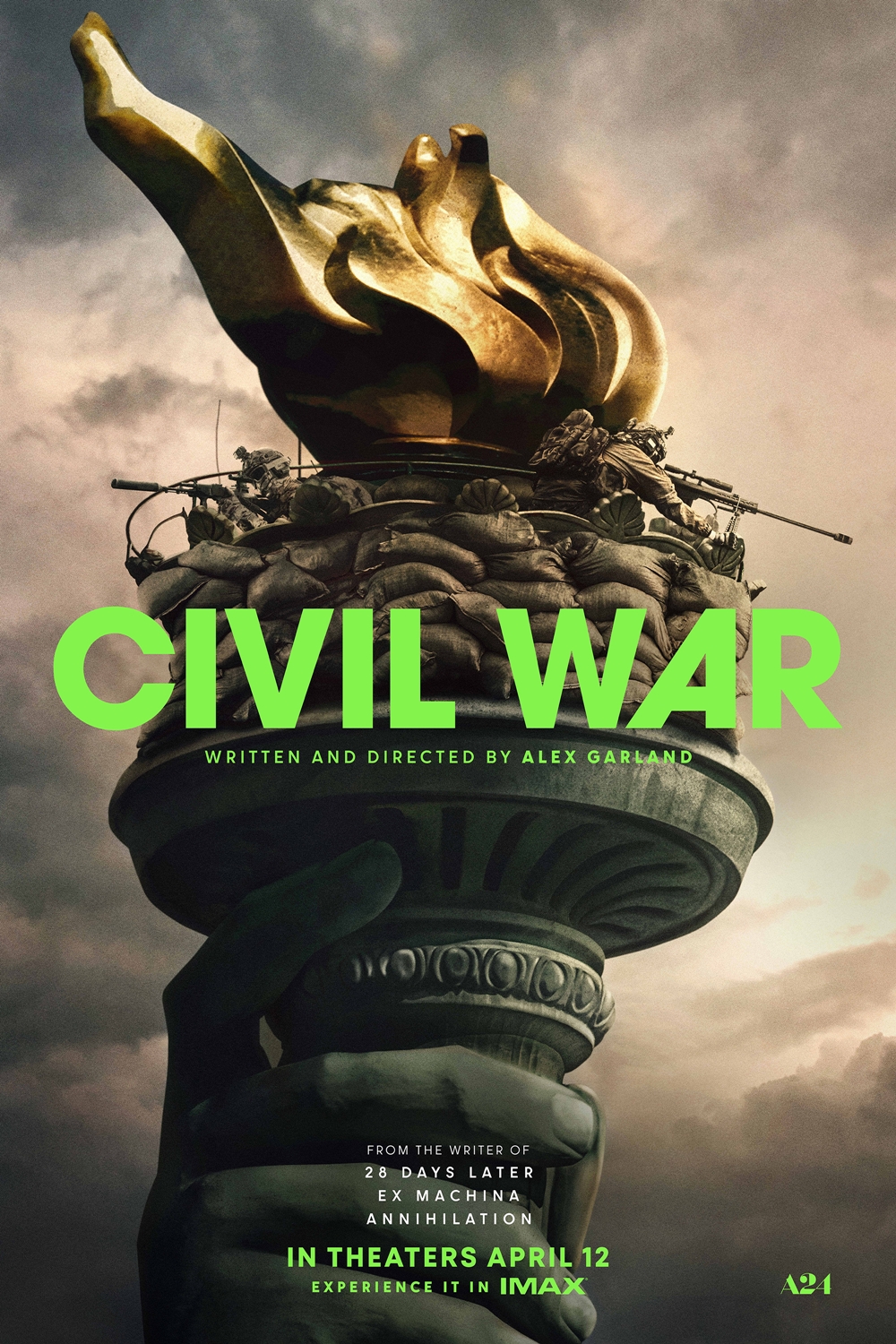

Image: Movie Poster via IMDb

Alex Garland tried to make an apolitical film about a political conflict and it turned out about as well as you’d expect it to. The apolitical nature of the film is not the issue so much as the way in which it maintains its neutrality: by withholding as much information from the audience as possible. What follows is a war movie where we don’t know how long the war has been going on, what it’s being fought over or what happens when it’s over. It’s a film without stakes that wants its audience to be emotionally invested without giving them anything to latch on to, that thinks ambiguity means being as confusing as possible and that thinks neutrality means removing motivations from its story entirely. As with all anti-war films, “Civil War” (2024) uses violence and death to try to make a statement, but when we don’t know who’s dying or why, and who’s killing them or why, all we see is an actor on the screen pretending to get shot. Removing all sense of belief results in a movie where violence is cheap and danger irrelevant. When war becomes a force of nature instead of a product of manmade decisions, it removes our responsibility and takes our need to care about the horrors it creates with it.

“Civil War” follows a team of four journalists in a not-too-distant future where America has been consumed by a civil war between three secessionist factions and the federal government. The journalists are in a race against time to travel from New York City to Washington D.C., where they plan to interview and photograph the president before the quickly approaching invasion of the secessionists. Among these journalists are PTSD-ridden war photographer Lee (Kirsten Dunst), her extroverted colleague Joel (Wagner Moura), their aging mentor Sammy (Stephen McKinley Henderson) and a young aspiring photojournalist named Jessie (Cailee Spaeny), who idolizes Lee. On their journey through the war-torn states, they encounter violent civilians, refugee camps, hostile soldiers and fellow journalists looking to capture the last days of America as we once knew it. As death becomes less and less avoidable the closer they get to D.C., Jessie learns what it takes to become a war photographer as the violence she witnesses begins to weigh on her more and more.

Garland’s idea of what a “journalist” is goes no further than a documentarian. It makes me wonder if he did any research before making this movie, or even just spoke to a journalist about the field. He presents them as robots whose only objective is to record by any means necessary, people who don’t think or care about what the picture they take is saying, or give any thought at all towards what they’re covering so long as they cover it. That’s not what journalism is, nor is it what journalists do, especially war photographers. You can’t photograph the image of somebody getting shot in the head and not put any thought behind it. Not only does that go against the ethics and artistry every journalist is taught in school, but against human nature itself. If you don’t have any feelings about what you’re covering then you shouldn’t be a journalist, you should be a stenographer. The role of the journalist is to provide a voice, and Garland presents an idea of journalism that is just aimless and directionless documenting, capturing somebody saying something without articulating it for your audience. Given the movie’s own lack of voice, Garland’s soulless documentarian idea of journalism seems to apply to his idea of filmmaking as well. No need to give your art a voice when you believe pressing a button on the camera is the only goal.

This detached attitude towards image capturing unfortunately seeps through to the film’s visuals. Aside from the forest fire sequence, which is admittedly beautiful, the majority of the movie looks like a commercial: high-quality cameras shooting shallow focus shots that mostly consist of characters sitting in a car or standing around on a highway or in an empty parking lot. Garland, who is British, makes no attempt to use American iconography beyond the final scene in the Capitol despite the movie being about the fall of America as we know it. A poster for the film features snipers camping in the Statue of Liberty’s torch, which is ironic because the Statue of Liberty isn’t even shown in the film despite the first 15 minutes taking place in New York City. The characters travel through iconic states such as Pennsylvania and Virginia, filled with the ghosts of our country’s founding civil war, and yet we never see any of it — just nondescript backroads and highways. While car culture might be America’s defining trait, the centering of it makes for an ugly, bland-looking movie. You get swallowed up by the monotonous tones of green and gray that dominate the screen.

The core issue with this film is a lack of belief. Garland is a British man making a movie about America and its politics, and it really shows. When asked by The Hollywood Reporter at the premiere of his film why Texas and California would form an alliance against the federal government despite historically being polar political opposites, he said, “If you cannot conceive of that then what you’re saying is your polarized political position would be more important than a fascist president which, when you put it like that, I would suggest is insane.” This naivety towards our country’s petty politics could only come from the outside. That insanity is what defines America. Garland’s lack of understanding of the depth of our petty evangelism is exactly why “Civil War” doesn’t work. It imagines war as a passive instinct rather than something driven by symbols. As an audience member watching these people kill each other, I wasn’t thinking about how awful it was that they were killing each other. I was asking, “Why?” Garland doesn’t care about the why and, as a result, his film leaves me feeling and thinking nothing. Like journalism, film requires the person behind the camera to care about what they’re showing us. Without investment, your audience can’t be invested either. A hollow image elicits a hollow reaction.

Elijah Fischer is a second-year English major. AF997636@wcupa.edu