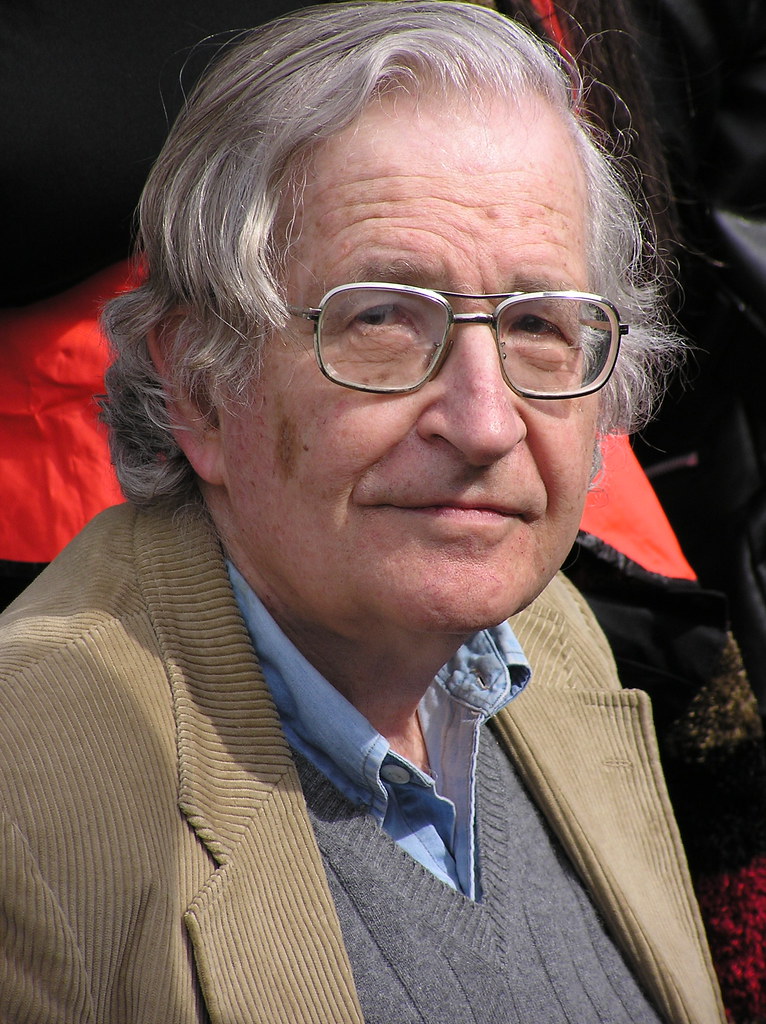

Photo: Duncan Rawlinson (CC BY-NC 2.0) via Flickr

Last Thursday, famed intellectual and political dissident Noam Chomsky gave a talk via video-chat at West Chester University. For those who are unfamiliar with him, Chomsky is something of a renaissance man; a professor at Massachusetts Insitute of Technology since 1955, now emeritus, he is responsible for paradigm shift advances in linguistics, philosophy, sociology and political science, and is said to be one of the most cited scholars alive in many fields of academia. News sources of every stripe and medium have interviewed him for his scalding-hot takes on the geopolitical crisis of the time, and he continued to do so during his talk in the Madeleine Wing Adler Theatre.

For a summary of the talk, you can read my other article in the News section, but suffice to say, Chomsky gave a grim diagnosis of our political problems, warning us of imminent societal collapse from either climate change, nuclear war or both. While some may have been shocked by his biting condemnation of the political status quo, those familiar with Chomsky were not surprised by his stalwart radical stances.

Chomsky has a storied past of activism and writing in politics, primarily as a ruthless critic of American imperialism, capitalism and mainstream news media. In between the occasional ground-breaking advancement in linguistics, Chomsky has written dozens of books on politics, primarily on the atrocities committed by the United States in the war-torn Southeast Asia, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and Western media acting as propagandists.

While attending a short talk at West Chester or reading a single Op-ed is insufficient to fully grasp his intellectual impact, Chomsky may be best understood through the political ideas that inform his worldview. Chomsky himself avoids the creation of a precise, singular political theory, but generally follows the mantra of the French Revolution that is widely popular in leftist politics, “Liberty, equality and fraternity,” or perhaps better understood as “community.” Chomsky describes himself as a libertarian socialist or anarchist; he detests most world governments, certainly the explicitly capitalist countries such as America, but also self-proclaimed socialist countries which do not meet his criteria for “economic democracy,” such as Soviet Russia under Stalin and modern day China.

Contrary to some on the far left, Chomsky also firmly abides by traditionally liberal Enlightenment values such as freedom of speech and association; in fact, he claims his libertarian socialist views are a natural result from such values. Chomsky regularly defends people he despises in order to abide by his principles, such as Walt Rostow, the National Security Advisor to President Johnson. Rostow was a key architect of the Vietnam War, which Chomsky is vehemently critical of, but when it was thought MIT might deny Rostow a position because of his explicit American patriotism, Chomsky threatened to protest. However, that will certainly not stop him from figuratively tearing people like Rostow apart in one of his many books on the Vietnam War.

Part of Chomsky’s charm is the interplay between what are usually two conflicting ideologies, a radical man of moderate demeanor. Chomsky, while a man who would likely feel right at home in the Paris Commune, wielding a rifle against the French Republic, is always soft-spoken and calm. He talks about dismantling capitalism and the evils of our corporatocratic government with a soft tone you would expect to accompany a pleasant conversation about your day, and describes the origin of toxic American gun culture the way an art critic might describe a painting.

Chomsky’s vocal delivery contrasts the severity of his claims so that one almost feels like it’s impolite to retort, although many have done so. As prevalent praise of Chomsky is, especially among leftist academics, so too is harsh criticism, usually by conservative academics. One notable example, David Horowitz, channeled his intellectual beef with Chomsky into a book, “The Anti-Chomsky Reader,” which features articles from himself and others who criticize what Horowitz called “the most devious, the most dishonest and … the most treacherous intellect in America.”

Some of these criticisms are certainly not without basis, depending on one’s viewpoint. Chomsky has historically let enemies of the U.S off the hook from his criticisms despite being totalitarian dictatorships and has even denied that political repression and mass killings have occurred in the Marxist regimes in Vietnam and Cambodia. More recently, Chomsky made great effort to avoid criticizing the tyrannical actions of Venezuela’s President Nicolas Maduro, saying on Ralph Nader’s radio show that Venezuelans can’t be blamed for supporting a tyrannical populist leader due to all of America’s manipulatory military actions in the country.

Personally, as much as I am interested in Chomsky’s massive body of work and support his perpetual dissidence, I have my own apprehensions with Chomsky’s legacy. I disagree with some of his political opinions, but more so his certainty that the ultimate apocalypse is right around the corner, as he and many others have predicted for decades. I also don’t think we should leave the state socialist governments in much of the Eastern hemisphere off the hook for their horrible actions past and present, even if America and the West are also liable for plenty of criticism. However, Chomsky’s legacy, though not complete, will certainly be remembered as that of an intellectual giant that influenced our generation, earlier generations and who knows how many generations going forward. He certainly influenced me, and to see the man himself (sort of) in person is a memory I’ll hold onto for a long time.

Alexander Habbart is a fifth-year student majoring in math and philosophy. AH855541@wcupa.edu