Image: By Olivia Schlinkman

You peer through the blinds. You don’t recognize the person swaying side to side atop your welcome mat, admiring your hanging begonias. Bundled up in a jacket, they have a stack of small papers at their side and a circular pin atop their coat.

Do you answer?

It’s mid-October — answering the door would mean letting the cold wind into your warm, snug home. The dog would surely go crazy upon seeing someone new at the front door. Plus, you already have an inkling of what they’ll say:

“Hello, do you have a voting plan for this year’s upcoming election?”

According to Vox, residents answer about one-fifth of doors knocked on by political canvassers.

Yet studies have shown that canvassing has the capability to mobilize at least 4% of contacted residents to vote.

The number might not sound like a whole lot. But, in the intensely polarized political realm that the U.S. currently navigates, such a demographic might just be a deciding factor in electoral outcomes, especially in key swing states like Pennsylvania. Recent polls regarding the outcome of the 2024 Presidential Election have placed candidates Kamala Harris and Donald Trump neck-and-neck.

And at West Chester University (WCU), students are taking advantage of that fact.

Watching, to tabling, to canvassing

Angelina Stambouli keeps busy. A 20-year-old junior at WCU, Stambouli spends her days copy editing for WCU’s student newspaper, The Quad; writing for Her Campus; attending Delta Phi Epsilon sorority events and she always finds time to hang out with her roommates and friends.

Lately, she’s been finding time to volunteer politically, too.

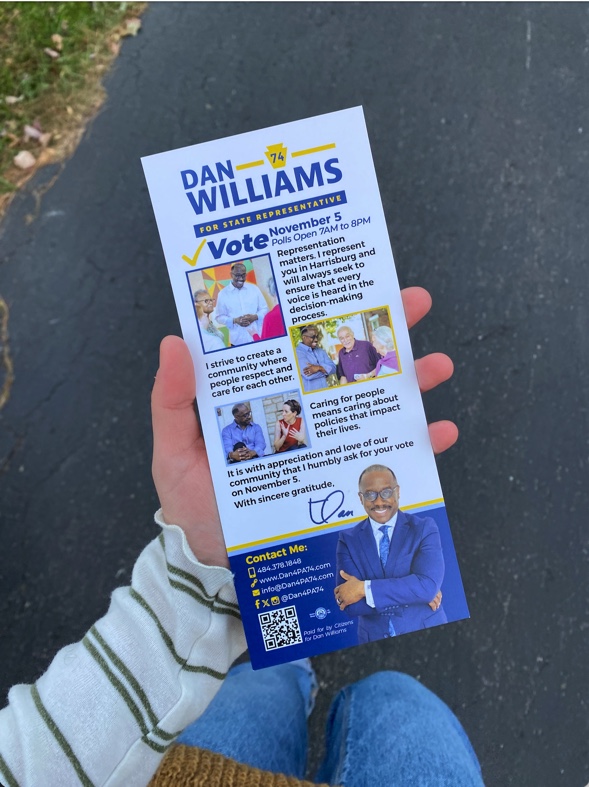

Stambouli has been working as a political canvasser throughout the Chester County region since mid-September. Vice President of the WCU Democrats, she has been campaigning up and down the ballot on behalf of numerous local and national Democratic candidates, including PA Senator Carolyn Comitta, PA Representative Malcolm Kenyatta, PA Representative Dan Williams and the Harris-Walz presidential ticket.

Growing up, Stambouli was always tuned in to politics a bit more than the typical kid — she grew up around a family of diverse political ideologies and was often exposed to news and current events. But the true turning point that sparked Stambouli’s passion for politics was the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic and the great deal of controversy and polarization it brought.

“Being home with my mom and my cat, watching the news every day, [seeing] what’s going on with the world…” Stambouli said. “That’s also when I decided I wanted to be a reporter or news anchor.”

As a freshman at Gettysburg College, before transferring to WCU her sophomore year, Stambouli took part in tabling with the campus democrats. There, she helped students stay informed and register to vote, which she attributes as being one of her first tastes of political involvement.

In Chester County, Stambouli has been working door-to-door canvassing or phone banking shifts (calling residents to speak about their voting plans and registration status) about two to three times a week and has most frequently been stationed in Downingtown, Caln and Thorndale. The typical canvassing shift consists of anywhere up to 30 houses for Stambouli to visit, with the goal of speaking with constituents to gauge their likelihood of voting. Stambouli asks residents about whether they have a plan to vote this November, whether they will vote in person or with a mail-in ballot, and if they know where their polling location is.

When some people see canvassers on their doorstep, they may find themselves preparing for the volunteer to sell a candidate to them. But Stambouli says that the goal of canvassing isn’t persuasion — it’s mobilization. Her job isn’t to convince residents to vote for a specific candidate, though she’s happy to share details about a candidate’s ideas and platforms. She and other canvassers want to help people realize the importance of their voice and the impact they can have on the issues they care about and to ensure that they are well-informed when taking that step.

“No matter what your beliefs are, whichever way you lean, I think it is just as important to register, make your voting plan, ask your family and friends [about their plans],” Stambouli said. “Just make sure you use your freedoms, your rights, to decide you and your friends’ futures.”

Learning while informing

Stambouli quietly cracks open the house’s front porch door. Between the inch-wide opening, she slips two pieces of campaign literature — smiling politicians’ faces await the resident’s return. With her work at this house done, she lightly shuts the door and slips off the front porch.

“I feel bad if I make noise and wake up the dogs.”

She’s come to learn this after dozens of previous door knocks have been met with a bombardment of barks. She’s nearly perfected the time to wait before concluding that the resident isn’t going to answer the door — she waits a little over 10 seconds. And though she calls herself an introvert who was initially intimidated by the idea of striking up conversations with strangers about politics — of all topics — Stambouli has warmed up to the process.

“You can’t take things personally.”

When canvassing, you never know who will open the door. They may be Republicans. They may be Democrats. They may dislike politics so much that they seem indifferent to the conversation altogether. Sometimes, residents won’t even come to the door — Stambouli has become accustomed to conversing via Ring doorbells.

But every few houses, she gets to put her skills to good use.

“There’s people who do ask for [the literature], who say, ‘Oh, my husband or wife would like this, or I could give it to my friends.’ Or, ‘Can you tell me a little bit more about this candidate? Because I do want to vote but I don’t know much about this person,’” Stambouli said.

When things like this come up, she gladly tells residents more about what candidates are doing in their district, what their platforms are and where the resident’s nearest polling location is.

To Stambouli, knowing that she’s helping even a little bit is fulfilling.

A route toward unity

For canvassers like Stambouli, the job of campaigning can be a lonesome one — many unanswered doorbells and “Beware of Dog” signs pepper a canvasser’s route. It can be challenging to not take a person’s disinterest in discussing politics personally. Engaging in a conversation where a resident is of an opposing ideology and is fairly adamant about their stance can be difficult.

Yet the process, she has found, is supporting unity and connection throughout her community.

“If people feel scared or anxious, which I do, about the election, you feel less alone in seeing just how many people share your beliefs, no matter what side of the aisle you’re on,” Stambouli said. “It’s good to know there’s people, different ages, different gender identities, who feel the way I do and have the same concerns as I do.”

And though her job description is technically the informer and motivator, sometimes she finds herself learning from the residents she visits, too.

“The few interactions I have had, I’ll probably remember for a while,” Stambouli said. “There’s [some] where, [I think,] that was really meaningful to know that, like, ‘This candidate on the ballot helped my wife and I with COVID-19,’ it’s nice to have that exchange.”

Getting out the youth vote

By 6 p.m. on a recent October afternoon, Stambouli’s feeling accomplished, having successfully visited nearly every house on her route. Throughout the afternoon, there were many Halloween decorations in yards, many Ring doorbells, many pamphlets distributed — and many older individuals. Of the roughly two dozen houses she canvassed, no college-age students answered their doors.

The act of canvassing itself often has few college-age volunteers. Zippia estimates that 65% of canvassers are over 40 years old and Stambouli says, in her experience, that it is often more millennial-aged individuals who canvas.

Stambouli admitted that door-to-door canvassing is not the most effective means of reaching young voters. However, she has hope in other strategies’ capability to reach crucial demographics.

In her experience with phone banking, she’s found that young people are more likely to pick up the phone than answer doors, making it a more effective mobilization tool for youth. A 2020 study by the Pew Research Center found that individuals aged 18–29 were more likely than any other age group to answer an unknown phone call.

Additionally, she says that the possibility of political canvassing in WCU dorms is also on the horizon, where volunteers would knock on dorm room doors and inform WCU students about the upcoming election.

Not all college students have the time to volunteer with political organizations. Not everyone’s extroverted enough to speak to strangers about politics. But as a young person herself, Stambouli hopes that any and all people will get out and use their vote.

Olivia Schlinkman is a fourth-year Political Science student with minors in Journalism and Spanish.