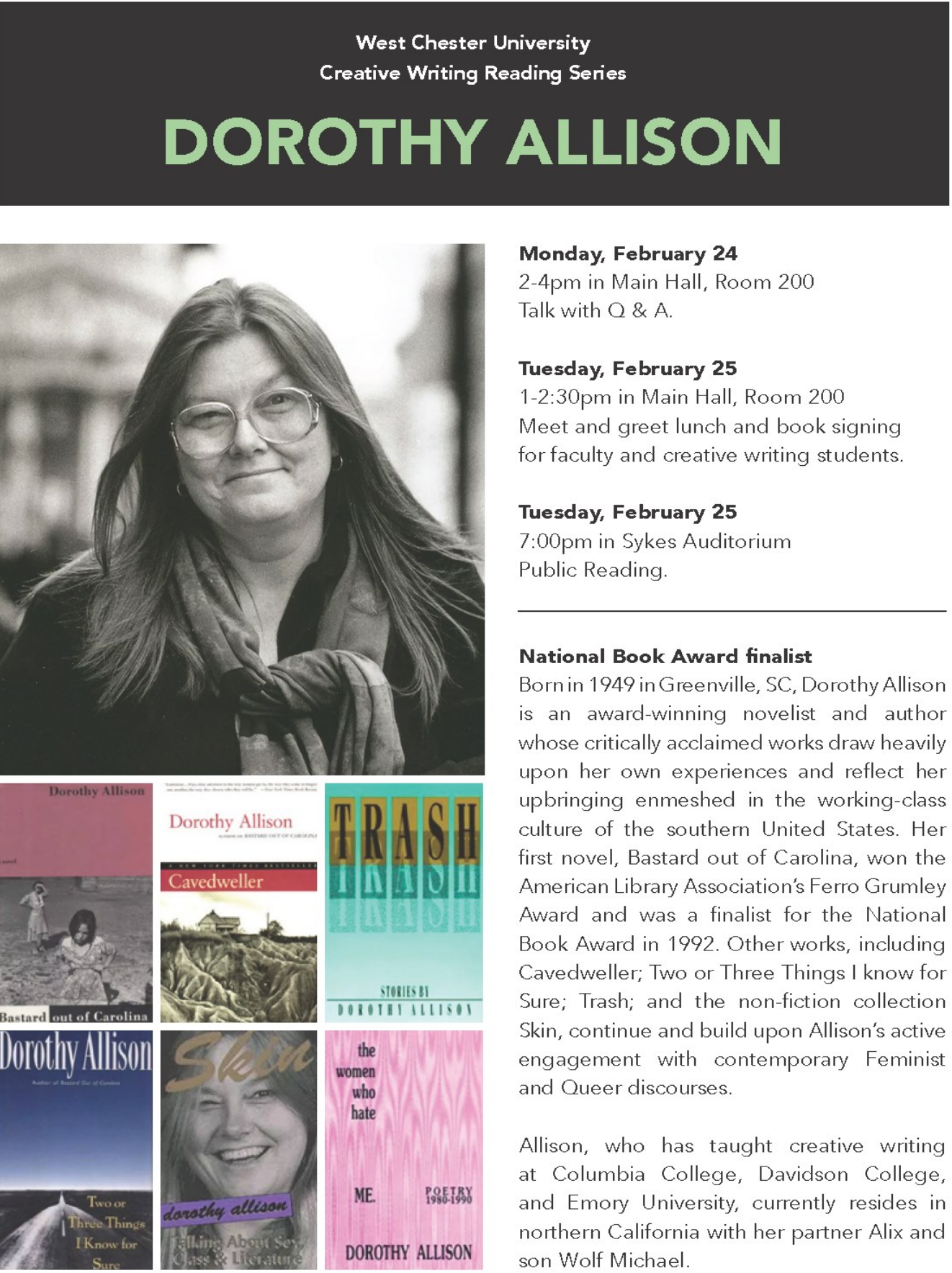

Photo courtesy of West Chester University Creative Writing Series.

Renowned author and National Book Award finalist Dorothy Allison visited West Chester last week as part of the university’s Creative Writing Reading Series. She was on campus for two days, holding a craft talk on Monday and two events on Tuesday; a meet-and-greet with creative writing students and faculty in the afternoon, and a public reading in the evening.

The reading took place in Sykes Auditorium at 7 p.m., where Allison was introduced by Professor Luanne Smith, who spoke about the influence that Allison had on her as a “baby writer” in the 1980s. Smith was born and raised in a working-class town in Kentucky and, like Allison, draws heavily upon this background when writing. This was at a time however, when critics in the field denounced writing about working-class communities, calling it “K-mart fiction.” When Allison’s debut novel, “Bastard Out of Carolina,” was published in 1996, Smith recalls, it was a “hallelujah moment.” It was the first time she had ever felt validated as a writer.

Allison started by talking about her childhood love of science fiction and her affinity for Star Trek’s “Deep Space Nine.” She recalled that she wanted to have been born in a different world, and sci-fi was an escape for her. She was inspired by the descriptive language used in these stories and always tried to emulate it in her own writing. She also had some advice for the writers in the room: she encouraged them to “write me something your mama will be scared of.” She believes that the “uncomfortable is the best we all can hope for.”

She shared her short story, “Jason Who Will Be Famous,” which is about a teenage boy who dreams of being famous. He fantasizes about being interviewed on TV and idolized by his peers. This fame, he imagines, will come after being kidnapped and confined to a basement. He brainstorms about everything that he could accomplish in captivity: he could learn to play the guitar, write music and especially write poetry, the kind that “makes your neck go stiff.” He pictures himself getting in shape—he’ll have to get thinner with only the food his captors provide, and everyone keeps some old weights in the basement. When he’s famous, Jason reckons, his parents will finally recognize his talents. His mother always rags on him to work harder. His father left when he was a child and they don’t talk much. He imagines reconciling with him once he’s famous. As the story comes to a close, Jason hears a vehicle headed toward him and imagines it’s his kidnapper. Things have to change, he thinks. “God, God let it change.”

Afterward, Allison explained her inspiration for “Jason Who Will Be Famous.” She lived in a small town in northern California, a “little white trash town.” One day, while stopped at a red light, she looked around at the teenagers hanging around on the side of the road. She felt annoyed by them, calling one a “goddamn son of a bitch.” She hadn’t meant to say it out loud and was ashamed of herself. She started wondering about that kid, wondering “What does he dream of?” She started writing “Jason” that night.

There was time for a few questions and answers. A man asked Allison if rhythm was important in her writing. She answered, “Major.” She said that she was raised in the Baptist church and grew up on rock n’ roll, which she believes influenced the rhythm of her writing. She advocated for reading one’s writing out loud, explaining that “good fiction should be extended poetry.”

She asked herself in jest, “How did you become a writer, Dorothy?” She explained that her mother was one of 11 children. Each of her six sisters had eight to ten kids, so she had a lot of cousins. As the oldest girl, Allison was often put in charge of them. Many of them had a propensity for violence—she notes that several went to prison and that “they all deserved it.” She started telling stories, “terrible stories,” to occupy them.

She was the first member of her family to graduate from high school and received a scholarship to go to college. She felt like she didn’t belong among her wealthy peers and became depressed and suicidal. When she didn’t receive a scholarship to graduate school, she moved to Orlando and worked at a grocery store. Once, four teenagers came in to rob the store. One of them put a silver pistol to her head. She thought to herself, “I didn’t do anything.” They didn’t shoot her, and she recalled that she “was determined to do something” after surviving the robbery. This was the catalyst for her writing career, calling it a “come-to-Jesus moment.” She left all the “baby writers” in the room with one hope: that they too would have a come-to-Jesus moment.

Shannon Montgomery is a third-year English major with minors in creative writing and women’s & gender studies SM916394@wcupa.edu