- Early in the morning of Thursday, November 8, a student was assaulted by a man who had followed her home down an alleyway on S. High Street. A warning was later posted on WCU Public Safety’s website, but no email was sent out to students.

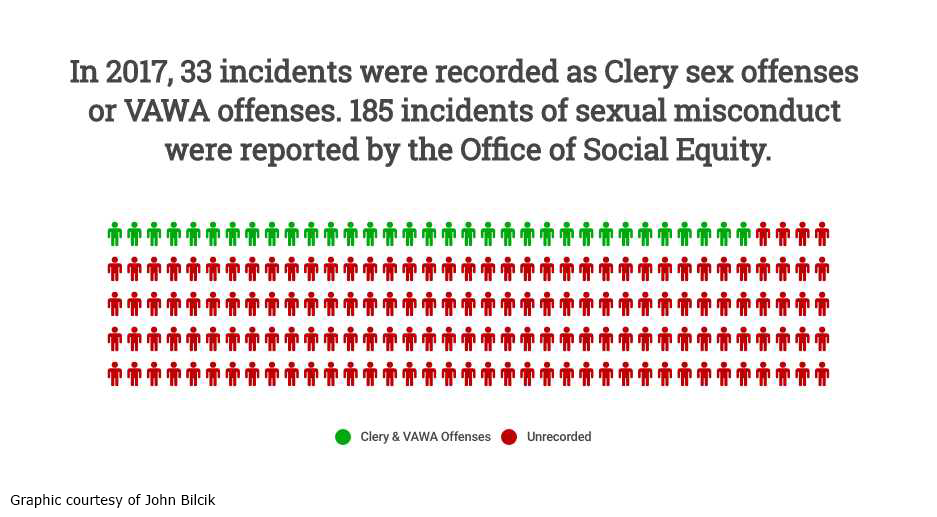

- The publicly released 2018 “Annual Security and Fire Safety Report” lists 33 cases of Clery sex offenses and Violence Against Women Act offenses, which are not exclusive to women, in 2017. Lynn Klingensmith, the director of the office of social equity revealed that 185 cases of sexual misconduct (which includes sexual harassment, assault and exploitation) occurred in 2017.

- Though progress is being made in advertising resources for sexual misconduct, resources such as the Center for Women and Gender Equity are mislabeled as “confidential” on wcupa.edu, creating issues for students who may want to share their stories confidentially but do not know where to go.

- At the moment, our university does not have a Sexual Misconduct Advocate in the Office of Wellness promotion, leaving students with a gap in sexual misconduct resources.

· · ·

In the past few years, sexual assault has become a trending topic in the news. With the #Metoo movement going viral in Oct. 2017 and waves of women coming forward with allegations against men like Harvey Weinstein and Brett Kavanaugh, media outlets are covering sexual assault cases in their daily reports. These constant headlines reflect the sad reality of sexual violence in the United States, with universities in particular housing a rape epidemic. The Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN) notes that women in college are three times as likely to be a victim of sexual violence than women of all ages and that 23.1% of female undergraduate students experience rape or sexual assault during their college careers. Men are also affected by these acts of violence, as 5.4% of undergraduate men experience rape or sexual assault (“Campus Sexual Violence: Statistics”). These statistics shed light on the need for colleges to address sexual violence head-on, but with such a pervasive problem and no one approach to remedy it, many universities are left scratching their heads.

Title IX in Action

In order to analyze a school’s sexual misconduct policy and procedure, it is important to understand how a school’s responsibility to handle sexual misconduct is grounded in Title IX requirements. Title IX states, “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance” (Title IX, Education Amendment of 1972). Though Title IX was created to address asymmetry in funding for National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) sports, guidance released by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights asserts that gender equality goes far beyond athletics. In 2001, guidance was introduced outlining a school’s responsibility to address sexual harassment, and in 2011, that scope was broadened to encompass behaviors that fall under sexual violence. According to the Office for Civil Rights, “a school has a responsibility to respond promptly and effectively. If a school knows or reasonably should know about sexual harassment or sexual violence that creates a hostile environment, the school must take immediate action to eliminate the sexual harassment or sexual violence, prevent its recurrence and address its effects” (Know Your Rights: Title IX Prohibits Sexual Harassment and Sexual Violence Where You Go to School). Additionally, schools must have and distribute a policy against sex discrimination, have a Title IX coordinator and make the procedures for students to file complaints of sex discrimination known. West Chester University’s Title IX coordinator Lynn Klingensmith affirmed this notion when describing her role on campus. She explained, “In a more micro sense, we respond to, address and mitigate instances of sexual violence and harassment.”

Title IX: A Work In Progress

While ensuring gender equality may seem like a given, universities struggle to find the best ways to protect their students and interpret Title IX guidance. To make matters even more confusing, United States Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos rescinded Obama-era Title IX guidance in 2017, resulting in mixed reviews from Title IX advocates and lawyers. Part of DeVos’s proposed rules include the option for a school to use a “clear and convincing” evidence standard in determining whether or not a person is guilty of sexual misconduct, a higher standard than preponderance. According to the New York Times, “among the most significant changes in the proposed rules would be the department’s move to clarify and narrow the scope of complaints that schools are obliged to investigate,” noting that institutions would only be required to investigate “formal complaints that are filed with an authority figure, and no longer require that schools investigate complaints alleging conduct that occurred off campus or outside their school-sponsored programs” (“Proposed Rules Would Reduce Sexual Misconduct Inquiries, Education Dept. Estimates”). Regardless of one’s political affiliation, Title IX is controversial. In the midst of all the confusion that surrounds Title IX, it became evident to me that in order to fully understand our university’s sexual misconduct policy, I would have to talk to the staff and faculty who know it best.

Issues with Transparency: Our University’s History

I started by consulting psychology professor Dr. Deborah Mahlstedt about some of the issues our university has encountered in the past. During a conversation about the need for transparency with sexual misconduct reports, Dr. Mahlstedt referenced uproar on campus that occurred between 1995 and 1997 in response to allegations of professors sexually harassing students going unaddressed. “We didn’t know what was happening with student complaints,” she explained. “They would go to Social Equity and they would essentially just disappear. So, a group of faculty and students organized something called Campus Action Against Sexual Harassment. From that task force, it was very clear that students are at a disadvantage. If it was a faculty member they were challenging, the faculty member had representation from the union.” Dr. Mahlstedt also discussed some of the specific ways that the task force supported students, such as creating sexual misconduct advocates who organized and assisted students whose complaints were not being appropriately handled. In this way, students were given the voice that was taken from them and were emboldened to hold WCU administration responsible for protecting its students. After talking with her about our university’s history, I became increasingly aware of the need for transparency in our administration as well as the importance of advocacy in supporting survivors.

Issues with Transparency: Problems in the Past

In an attempt to find more information about our university’s past controversies, I consulted the web. After doing a bit of digging, I found an article from Security Info Watch titled “Playing with Statistics on Campus Crime Data.” The article, written in 2006 by Patrick Kerkstra, reveals that figures reported in WCU’s 2003 and 2004 Clery statistics were startlingly inaccurate. The Clery Act, signed in 1990, “is a federal statute requiring colleges and universities participating in federal financial aid programs to maintain and disclose campus crime statistics and security information” (Federal Student Aid, “Clery Act Reports”). Though the act was designed to create transparency, West Chester University’s campus crime data from 2003 and 2004 demonstrate classification errors that contribute to underreporting. Kerkstra explains that after a Philadelphia Inquirer investigation of campus police logs turned up incidents not reported in Clery statistics, WCU was forced to fix its low figures. Kerkstra writes, “A single sexual assault in 2003 and 2004 morphed into 14 attacks, including ten in residence halls.” All in all, the review led to the relabeling of almost 60 crimes. Prior to the relabeling, the image of West Chester University was one virtually untouched by crime, and while some may argue that security goes beyond numbers, transparency remains an issue. Unfortunately for students, underreporting is a nationwide problem. Eighty-nine percent of colleges reported zero rapes in their 2015 Clery Act Reports, demonstrating that students do not feel comfortable coming forward with reports or schools are shirking their duty to col lect and report crime data accurately. I attempted to verify the miscount from the past with Public Safety and inquire about what is being done now to ensure accurate reporting, but did not get a response.

Asking the Administration: What Happened to the Sexual Misconduct Advocate?

With this information in mind, I attended a Town Hall meeting on Oct. 2, 2018 in Sykes. The Town Hall, hosted by the Student Government Association (SGA), featured the university’s President, Dr. Fiorentino, the Vice President of Student Affairs, Dr. Davenport, the Senior Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies, Dr. Osgood, and the Executive Vice President and Provost Dr. Bernotsky. I enlisted the help of Assistant News Editor Samantha Walsh and Managing Editor Olivia Bortner to ask several questions relating to sexual misconduct, and as soon as the SGA Senators finished their series of questions for the administration, the floor was turned over to the general public.

The first question I asked related to the official Sexual Misconduct Advocate position. The term Sexual Misconduct Advocate has had two different meanings during West Chester University’s lifespan, with the first being the previously-mentioned group of advocates that emerged from controversy in the mid-90s. The second is an official position located in the Office of Wellness Promotion that was designed as a confidential resource and provided ongoing support to sexual misconduct survivors. Prior to the Town Hall, I interviewed Emily Sheehan and Alicia Hahn from the Center for Women and Gender Equity. In this interview, Hahn noted that at the moment, there is no official Sexual Misconduct Advocate in the Office of Wellness Promotion. I asked administration about the status of the position and why, if Hahn is correct, this position does not exist. Dr. Davenport responded promptly and succinctly: “The position still exists.” I later confirmed with multiple faculty members and staff that the position is indeed vacant, and though perhaps the title still exists, nobody is fulfilling it. I scheduled an interview with Dr. Julie Perone, a psychologist at the Counseling Center who was also in attendance that night, to discuss this topic in more detail.

Asking the Administration: What Constitutes Imminent Danger?

My next question concerned timely warnings. Timely warnings fall under the Clery Act, which, as previously noted, requires that universities disclose campus crime. Before Walsh got the chance to relay my inquiry about what constitutes an imminent threat to the campus community, another student posed a similar question. The student remarked, ““I remember a time when we would get timely warning notifications when there were sexual assault incidents or shooter incidents in the West Chester area, and I’m just wondering why we haven’t been getting those.” Interim Director of Public Safety and Chief of Police Jon R. Brill stood to address this concern. Chief Brill first clarified Clery Act requirements. “The Clery Act requires us to do a timely warning for any incident that can provide an imminent danger to the campus community based on circumstances that happen either on or off campus…Timely warnings are specific to ‘Did a Clery crime occur?’ And ‘Did it occur in a Clery geography?’” In terms of the decision making process that underlies the alerts, he explained, “It’s a committee process. When I get information, I contact several members of the cabinet, in addition to our Title IX coordinator, and we make a decision whether it qualifies. We agree on the message that should be sent out and when it should be sent out. So, these things are all taken into careful consideration.” Still concerned about the few sexual assault and sexual misconduct warnings received, I attempted to reach out to a detective from Public Safety to set up an interview. Unfortunately, I have yet to receive a time for the interview or a response to the list of questions I sent regarding the process of investigating complaints and Clery Act requirements. It’s also worth mentioning that around 6:45 p.m. on Wednesday, Nov. 7, an indecent exposure incident occurred near the intersection of E. Rosedale Ave. and S. Matlack St. While it appears some students received text message alerts regarding the incident, I, as well as others, received no alert. Additionally, Public Safety posted a timely warning online regarding a sexual assault off campus that occurred Thursday, Nov. 8 after 1:00 a.m. A student was sexually assaulted in an alleyway after a man approached her on S. High St. and followed her on her way back home. I wonder, why was the warning posted on the WCU website, but an email never sent out? How are students being kept safe by these alerts if they never receive them on their personal devices?

Asking the Administration: Clery Statistics – Why so Low?

As the Town Hall was wrapping up, Bortner managed to raise one more question. I formulated this question in an attempt to better understand why Clery statistics fail to reflect the real number of sexual misconduct occurrences at universities across the country. Bortner asked, “Does a police report have to happen for things to make it into the Clery report?” Chief Brill explained, “We don’t have to have a report from the police department in order to include that in our Clery Statistics.” His answer, like some of the others, left me even more confused. According to RAINN, only 20% of female students report sexual assault to law enforcement (“The Criminal Justice System: Statistics”). If a police report is not required in order for an incident to make it into the Clery Statistics, then why are the numbers so low? Were there really only four rapes on campus in 2017, or do the statistics fail to capture what really goes on behind closed doors? (Clery Act – Criminal Reporting on Main Campus)

An Interview With Our Title IX Director Lynn Klingensmith

My first interview post-Town Hall was with our Title IX Director Klingensmith. To start our interview, I requested that she illuminate what the process of reporting sexual misconduct looks like. Klingensmith explained that the Office of Social Equity responds to a sexual misconduct complaint within 24 hours. The two big questions are “are you okay?” and “what do you need?” A lot of times, students want classes and residences changed to avoid their assailant or harasser, and this is where the Registrar and the Director of Residence Life can make accommodations. I also asked what the key differences are between the school’s processes and a criminal investigation, curious as to whether or not the way a school treats a complaint affects the way it is reported to the public. Klingensmith disclosed that in a criminal trial, there has to be no doubt that the accused actually committed the crime, while cases at the university can be processed with far less evidence. She noted that “West Chester has always used preponderance,” meaning that the greater weight of the evidence dictates whether the outcome is in favor of the complainant or the respondent.

Clery Reports: Narrow Definitions and Low Numbers

I then prodded for more information about why only some instances of sexual misconduct make it into the Clery statistics. Upon examination, Clery Reports have four different categories under sex offenses, including rape, fondling, incest and statutory rape. Out of these categories, five rapes were reported on campus in 2015, with five rapes also reported in residential facilities and one on public property. Additionally, there were a total of four fondling incidents (two on campus and two in residential facilities). In 2017, there were four reports of rape on campus and three in residential facilities with no reports of other sex offenses. Violence Against Women Act offenses are also included in Clery reporting and are defined as domestic violence, dating violence and stalking. In 2015, there were 34 accounts of VAWA offenses, and in 2017, there were 26. Locations of the offenses include on campus, residential facilities and on public property. The combination of Clery sex offenses and VAWA offenses for the previously listed geographic locations would be 49 in 2015 and 33 in 2017. However, the actual number of sexual misconduct reports that the Office of Social Equity received is very different. Sexual misconduct at WCU is defined as sexual and gender-based harassment, sexual assault, dating and domestic violence, sexual exploitation and stalking. Klingensmith revealed that in 2015, there were 75 reports of sexual misconduct on campus with that number jumping to 185 in 2017. High numbers are not necessarily bad news, as they likely reflect increased awareness of resources on campus rather than an increased number of incidents. (Note: these numbers encompass all behaviors defined as sexual misconduct under our university’s policy.) What concerns me more than the spike in numbers is the fact that despite the intention to create transparency, Clery statistics alone do not come close to the reality of sexual misconduct on college campuses. In terms of the low numbers in the Clery Statistics, Klingensmith pointed to the narrowness of Clery definitions as well as the limited geographic locations affiliated with the university that require crime reports. The university’s definition of sexual misconduct is broader than the offenses listed under Clery crimes, contributing to possible discrepancies. Additionally, statistics do not always represent incidents shared with confidential resources. Klingensmith explained that many reports go to the Student Health Center, but because it is a confidential resource, all she knows is that something happened. Adding to the few reports is the fact that many individuals forgo reporting sexual misconduct altogether. The combination of restrictive Clery definitions, the use of confidential resources and a lack of reporting on the part of the victim means that Clery statistics underestimate sexual misconduct on college campuses across the country.

Room to Grow

Finally, we broached the Sexual Misconduct Advocate position. Klingensmith affirmed Hahn’s statement, noting that at the moment, we do not have anyone fulfilling this role. Klingensmith admitted that “right now, we are at a crossroads,” and that “key people” are missing. She did assert, however, that “we recognize the need for additional resources and services and we are working to address that,” leaving me with hope for progress in this realm.

An Interview with Licensed Psychologist Julie Perone

As previously mentioned, I also followed up with Dr. Perone, professor and Chair of the Center for Counseling and Psychological Services. She first confirmed Hahn’s statement that the Sexual Misconduct Advocate position is not currently fulfilled and then detailed what a Sexual Misconduct Advocate is and why they are so critical. Dr. Perone explained that a Sexual Misconduct Advocate is someone who is supportive and understanding of a survivor’s trauma and who can accompany the individual throughout the process of pressing charges if they decide to do so. At a university level, the advocate(s) would not be a 24/7 hotline but rather an additional measure to ensure that the survivor feels supported and in control of the circumstances that follow an incident. On their importance, she remarked, “I think having someone there is almost critical,” highlighting the impact of advocacy for someone who may feel silenced and victimized.

A Lack of Resources: The Student to Counselor Ratio

We ended the interview with a conversation about the student-to-counselor ratio at West Chester University, something that is crucial in a school’s commitment to student welfare. Our university’s Counseling Center is fully accredited through the International Association of Counseling Services Inc. which recommends one therapist per every 1,000-1,500 students. Dr. Perone noted, “Here at WCU, it is recommended that we have anywhere from 12 to 17 full-time therapists to meet the mental health needs of our student population. At this time, we have 10 full-time counselors (a combination of Licensed Professional Counselors and Psychologists), but of those 10, one, Ms. Katie Bradley, is a Certified Advanced Alcohol and Drug Counselor (CAADC) as well as an LPC, so the majority of her clinical time is devoted to students who present or are mandated for substance abuse counseling. We do have a training program here, but only two of the trainees are full-time; they do hold doctorates and are providing clinical work under the supervision of licensed psychologists here.” While the Counseling Center wants to provide services to every student that needs them, she revealed that with a ratio such as theirs, there are limitations. “With limited resources, that means that those students who wait until their symptoms or situations worsen will not be able to receive services here because we will be at capacity,” she explained. She also expressed the desire for students to be more vocal about the growing demand for mental health services on campus, reminding students that even if you do not require counseling services, it is possible that someone you know does. For survivors of sexual misconduct, support is crucial, and having a greater number of trained professionals could help ease the demand of students seeking services.

Concern Number One: Where are Our Advocates?

With all of the information that I acquired from these sources, I narrowed down my concerns to a few crucial topics: advocacy, transparency and visibility. According to Dr. Mahlstedt, the absence of the Sexual Misconduct Advocate is a major issue. She expressed, “There needs to be more advocacy for students coming forward. It’s a shame that by not creating visibility, students are alone.” While Dr. Davenport’s response to my question may have created uncertainty as to whether or not the position is currently being fulfilled, conversations with faculty and staff demonstrate that we do indeed have a gap in resources. These same conversations also leave me with hope that there will be some significant changes in the realm of advocacy; though as students, it is up to us to hold the administration responsible for going through with these changes.

Concern Number Two: The Need for Transparency

In the realm of transparency, I am wary of the misleading nature of the Clery statistics. Schools with fewer crimes reported in the Clery Statistics may not actually be any safer, as low numbers likely reflect errors in counting crimes or a lack of encouragement for students to come forward. But unfortunately for sexual misconduct survivors, underreporting comes at a cost. Dr. Mahlstedt confirmed from her work with the Campus Action Against Sexual Harassment task force that “transparency and visibility go hand in hand. When people heard students coming forward, more and more students came forward. We know that there is what we call the ‘invisible victim,’ and I don’t think there is a lot of encouragement for the invisible victims to come forward.” Klingensmith noted an increase in sexual misconduct reports from 2015 to 2017, likely due to a greater awareness of resources, but according to Clery statistics alone, reports have gone down. Even if the narrowness of Clery definitions is the cause of such low reports, the campus community would greatly benefit from a more comprehensive look at the real numbers that fall under WCU’s definition of sexual misconduct. Dr. Erin Hurt, English professor and Green Dot Educator, explained the benefits of presenting campus crime data publicly: “Students have many questions about what these numbers are and how they are calculated. It would be useful if the university could hold a public forum where they presented the Clery numbers as well as the number of sexual assault complaints made to Social Equity, which would give students the chance to ask questions about the data and what it means.” If students got a chance to glimpse the real number of sexual misconduct reports in a public forum, then they may feel less alone and more willing to share their experiences, allowing the university to better understand the needs of its population. Because formal complaints only reflect a small percentage of actual incidents, some advocates have also encouraged the use of Campus Climate Surveys. Though the endeavor is costly and getting adequate sample sizes can be challenging, self-reporting incidents of sexual misconduct may help paint a clearer picture about the current state of our campus. I reached out to WCU’s Commission on the Status of Women in an attempt to find out more about campus climate surveys and the safety and security of women on campus, but have yet to be contacted about setting up an interview.

Concern Number Three: Visibility

When it comes to visibility, accurate reporting to the student body is a start. Properly advertising resources is also a crucial way to ensure that students know the kind of support that is available to them. Just last week, I saw a flyer in the library’s first floor women’s bathroom with false information about confidential resources. The Center for Women and Gender Equity was listed as a confidential resource for students who are victims of sexual misconduct, though Hahn mentioned that the Center is no longer confidential in our interview earlier this semester. I do not know when the transition from confidential to non-confidential took place, but my ignorance only serves to illustrate the problem. Students need to know who they can talk to in complete confidentiality to avoid the revictimization that may occur if they unknowingly share their story with a mandated reporter. Under WCU’s “Resources for Victim/Complainants” web page as well as several other places on the WCU website, the Center for Women and Gender Equity is still listed as a confidential resource, demonstrating that our administration needs to be more vigilant about supporting survivors and communicating changes in resources. To clarify, the only confidential places on campus where students can share sexual trauma without fear that it will be reported are the Counseling Center and Student Health Services.

Sexual Misconduct: Starting the Conversation

Despite some areas where the university can improve, the Center for Women and Gender Equity has been making strides in generating conversation about sexual misconduct. The CWGE, with support from the Office of Social Equity, recently distributed flyers containing sexual misconduct myths and ways to support sexual misconduct survivors across campus. Additionally, the CWGE held West Chester’s first It’s On Us event on Oct. 24, 2018. The event encouraged students to recognize the importance of consent and the need to be an active bystander in situations where consent cannot be given. Utilizing community-based approaches such as this is one of the ways that advocacy and visibility can be improved. By giving students a more realistic look at the reporting that happens on campus as well as advocacy and support in the form of on-campus resources, students who have experienced sexual misconduct can feel more empowered and in control, a key component in helping them heal. And though Title IX may be confusing and controversial, when it comes to creating policy that ensures a safe space for all students, there can be no compromise.

· · ·

If you or someone you know is a victim of sexual misconduct, you can utilize these resources on campus and in our community:

24/7 Confidential Professionals:

- On-call psychologist may be accessed by contacting Public Safety [610-436-3311]

- Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network (RAINN) [1-800-656-4673]

- Crime Victims’ Center of Chester County (CVC) [610-692-7273]

On Campus:

- Counseling and Psychological Services: (610) 436-2301 *Confidential and Privileged Resource

- Student Health Services: (610) 436-2509 *Confidential Resource

- Title IX Coordinator/Social Equity Director: (610) 436-2433 *Non-Confidential Resource

Celine Butler is a third-year student majoring in psychology with minors in French and history. CB869017@wcupa.edu

Legislators should create a very stricter law against sexual misconduct.